Entrepreneurship is increasingly recognised as a pathway to inclusive and sustainable development. Yet, in developing nations like Nepal, systemic barriers such as gender inequality, geographic remoteness, and socio-cultural exclusion continue to prevent large segments of society, particularly marginalised women, from fully participating in the entrepreneurial economy.

This article tries to explore how an inclusive entrepreneurship ecosystem (IEE) can be designed to empower these people without disrupting their indigenous knowledge, lifestyles, and aspirations for happiness. Drawing insights from global frameworks and localised examples, it emphasises that inclusivity is not a mere add-on but a structural redesign of the entrepreneurial habitat.

Defining inclusive entrepreneurship

An inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem refers to a dynamic network of interdependent actors, institutions, infrastructures, and cultural norms designed to foster equitable access to entrepreneurial opportunities – particularly for historically marginalised groups. It goes beyond simply supporting business creation; it ensures that all individuals, regardless of gender, geography, ability, or socio-economic background, can participate meaningfully and sustainably in entrepreneurial activity.

Drawing on the International Labour Organisation and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), an inclusive ecosystem must be both mature – functionally integrated across services, markets, policies, and capital – and truly inclusive, removing structural barriers to ensure accessibility for all. This includes equitable access to finance, legal frameworks, skills development, market linkages, and cultural legitimacy for diverse entrepreneurs.

In the context of Nepal, inclusive ecosystems must acknowledge the indigenous entrepreneurial practices rooted in local culture, such as traditional Dhaka textile weaving in Tehrathum or herbal remedies in Dolpa or Lokta papers in Baglung. These micro-enterprises, often built upon tacit knowledge passed through generations, are frequently excluded from mainstream policy mechanisms. However, displacing these traditional models in pursuit of formalisation may undermine community well-being and identity.

In the context of Nepal, inclusive ecosystems must acknowledge the indigenous entrepreneurial practices rooted in local culture, such as traditional Dhaka textile weaving in Tehrathum or herbal remedies in Dolpa or Lokta papers in Baglung. These micro-enterprises, often built upon tacit knowledge passed through generations, are frequently excluded from mainstream policy mechanisms. However, displacing these traditional models in pursuit of formalisation may undermine community well-being and identity.

Inclusive ecosystem development should build upon localised systems, valuing indigenous skills and wisdom as foundational assets for inclusive entrepreneurship. As demonstrated by the Taobao village model in China, integrating digital tools and social networks to empower bottom-of-the-pyramid (BoP) entrepreneurs led to thriving rural ecosystems without uprooting community life. [For details, visit: https://www.emerald.com/cms/article/15/3/613/107568/Investigating-inclusive-entrepreneurial-ecosystem]. ICT, microfinance, and localised support networks can enable similar models in Nepal.

Enablers of IEE

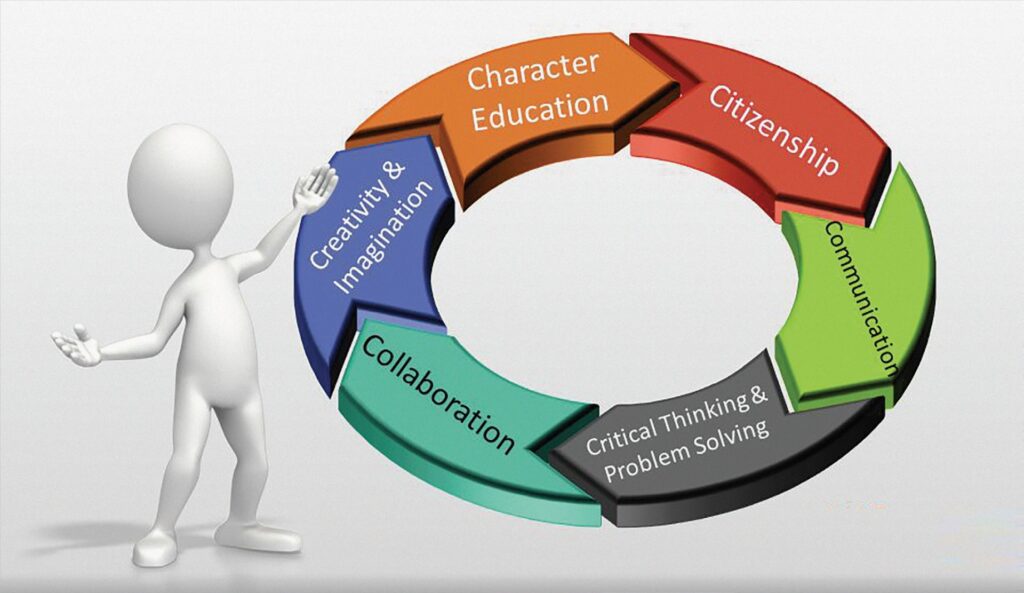

Promoting inclusive entrepreneurship in Nepal requires a multidimensional approach that addresses structural barriers while leveraging local assets, technologies, and community values. Below are five critical drivers that can foster a more inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem, particularly for marginalised groups such as rural women, indigenous communities, and informal micro-entrepreneurs.

- Human Capital Development: Many women and youth in remote regions possess valuable traditional knowledge, such as weaving, sewing, herbal medicine, or food processing, but lack access to formal entrepreneurial education. Tailored capacity-building initiatives that recognise and build upon indigenous skills can bridge the gap between informal expertise and sustainable business practices. Programmes that integrate functional literacy, business coaching, and leadership training – delivered in local languages and formats – are essential for converting potential into enterprise.

- Digital and Financial Inclusion: Drawing inspiration from China’s Taobao Villages, where digital platforms helped unlock the entrepreneurial potential of bottom-of-the-pyramid communities, Nepal can foster similar inclusion through mobile-based tools. FinTech platforms like eSewa and Khalti have begun to democratise access to digital finance. When coupled with targeted digital literacy training, these technologies can enable rural women to market local products, receive payments, and access micro-loans, thus breaking spatial and gender-based barriers.

- Inclusive Infrastructure: Inclusive ecosystems must decentralise access to critical resources, such as finance, training, and market linkages, by embedding services within local communities. Group-based lending model of microfinance, which offers collateral-free loans to women and micro-entrepreneurs, demonstrates the power of trust-based, community-embedded financial systems. However, ecosystem actors must work to align financial access with capacity-building and rights-based approaches of these institutions.

- Cultural Sensitivity and Social Norms: Successful entrepreneurship programmes must resonate with local values and collective identities. For example, in communities with strong collectivist traditions, mostly in rural Nepal, cooperatives and community enterprises are often more socially acceptable than individually-owned, profit-oriented businesses. By framing entrepreneurship as a community-serving activity (e.g., employment generation, preservation of heritage and indigenous wisdom, or local service delivery), initiatives can gain broader legitimacy and overcome social resistance.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) as an Enabler: Emerging AI technologies present new opportunities for democratising business support – offering tools such as market prediction, inventory optimisation, financial planning, and local-language chatbots for micro-entrepreneurs. However, to ensure equitable outcomes, these tools must be localised, co-designed with end-users, and delivered through accessible platforms. Without such contextualisation, AI risks reinforcing the digital divide by excluding those without digital literacy, infrastructure, or trust in formal systems.

Ecosystem Actors: Roles and Responsibilities

Building an inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem requires coordinated action among diverse stakeholders. Beyond formal institutions, informal networks, social capital, and community-based anchors play a critical and often underrecognised role in ensuring these efforts are contextually rooted, culturally accepted, and socially sustained.

- Government: The government plays a foundational role in setting the strategic direction for inclusive entrepreneurship. It must ensure policy coherence by embedding inclusion into national frameworks such as the Startup Policy, Industrial Enterprise Act, and the Microenterprise Development Programme. Furthermore, incentives, such as tax relief, seed funding, or preferential procurement, for innovations emerging from rural, indigenous, or marginalised contexts can help mainstream grassroots entrepreneurship. Government must recognise and collaborate with social anchors, such as women’s cooperatives, local organisations, and community leaders, who hold localised trust and can translate policy intent into community uptake.

- Financial Institutions and Microfinance Institutions (MFIs): Nepal’s financial institutions and MFIs must evolve from narrowly credit-focused models to become full-spectrum financial service providers for excluded entrepreneurs. This includes designing insurance products, offering effective financial literacy and enterprise-readiness training. Collaborative mechanisms with Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) to mandate a separate reporting on financial inclusion, by gender, geography, caste, and disability, can be helpful in this direction.

- Intermediaries and Support Organisations: Incubators, cooperatives, NGOs, and universities must act as community-based enablers, not centralised service hubs. Following the International Labour Organisation’s approach of mapping, co-design, and piloting, they should tailor support for indigenous and women-led enterprises, foster local mentorship, and improve market access.

- Development Agencies: NGOs and INGOs can play the role of catalysts by investing in inclusive infrastructure like developing digital centres, funding innovation labs and demonstration pilots, and facilitating public-private-community partnerships (PPCPs) that align with Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 8 (Decent Work) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequality).

- Corporate Sector: The private sector can embed inclusion into their corporate social responsibility (CSR) and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) agendas by supporting rural women-led incubators, integrating local producers into value chains, and offering mentorship through employee engagement. Partnering with social anchors like cooperatives and rural municipalities helps reach and uplift grassroots entrepreneurs.

Way Forward

An inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystem in Nepal must be built through strategic coordination and shared accountability among banks, incubators, intermediaries, private sector actors, and development agencies.

Commercial Banks and MFIs must expand their reach beyond urban centres and move towards relationship-based lending, inclusive savings instruments, and women-centric business advisory services. Institutions like Rastriya Banijya Bank or NMB Bank can integrate inclusive entrepreneurship into their CSR and financial inclusion portfolios.

Incubators and Accelerators need to decentralise their programmes and embed themselves within rural communities. They should promote mentorship, market linkages, and business readiness training that respect local knowledge systems while building entrepreneurial capabilities.

Private Sector Intermediaries like the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry, business development service providers, and fintech companies, should serve as crucial connectors, helping marginalised entrepreneurs navigate markets, regulations, and resources.

Development Agencies and NGOs can provide catalytic capital, capacity-building programmes, and evaluation frameworks that prioritise inclusiveness, well-being, and sustainability alongside profitability.

Policy and Regulatory Bodies like the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies, Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Securities and Nepal Rastra Bank must adopt a systems approach that mandates inclusive reporting, incentivises gender-equitable innovation, and reduces bureaucratic burdens for small and marginalised enterprises.

Inclusive entrepreneurship in Nepal is not merely about increasing the number of entrepreneurs – it is about fundamentally transforming the ecosystem to ensure it serves everyone. This transformation must be locally rooted in indigenous wisdom and rural livelihoods, while also being globally informed by proven models. It must be tech-enabled to bridge gaps rather than widen them, and equity-driven through deliberate support for those historically excluded. Every actor in the ecosystem must act as an enabler, unlocking pathways to dignity, innovation, and economic justice across the country. The ultimate goal is not to bring the marginalised into an existing mainstream, but to redefine the mainstream itself – one that embraces the wisdom, values, and enterprises of those who have long been left out.

Finally, in the spirit of Amartya Sen’s vision of development as the expansion of freedoms, inclusive entrepreneurship in Nepal must go beyond income generation – it should be a pathway to dignity, community belonging, and self-realisation. Nepal’s unique cultural and spiritual context allows entrepreneurship to serve not only economic ends but also social harmony and personal well-being.