- In the fiscal year 2022/23, the sum of money spent for overseas education increased substantially by 48.3 percent. Nepalis remitted Rs 100.42 billion from the country to cover the educational expenses of their children.

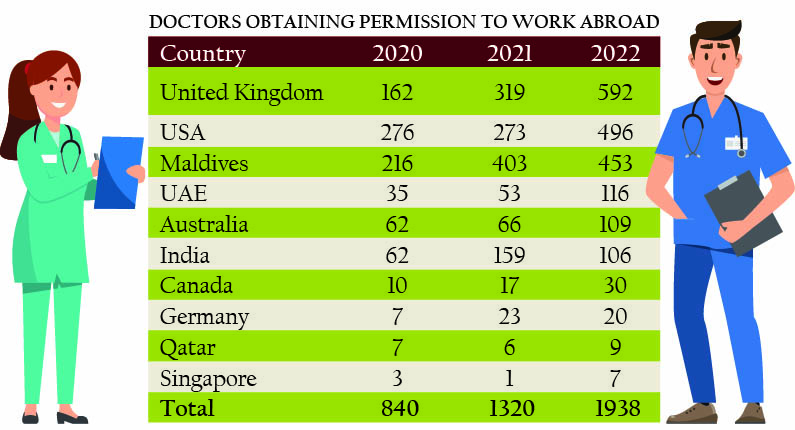

- In 2022, approximately 2,000 doctors sought authorization from the Nepal Medical Council to work abroad. This marks a significant increase compared to 2021 when only 1,327 doctors obtained such permissions.

- In the hospitality sector, it has become increasingly difficult for hotels and restaurants to secure skilled personnel for kitchen, food and beverage, and housekeeping roles. The five-star hotels in Kathmandu saw 30 percent of their experienced workforce migrating abroad in the last two years.

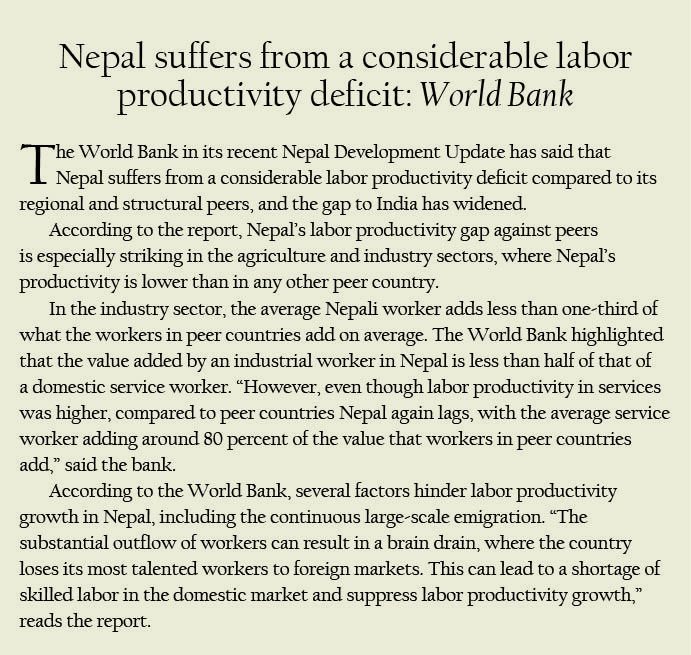

- The continuous large-scale migration from Nepal, according to a new World Bank report, has hindered the country’s labor productivity growth. Nepal’s labor productivity gap is particularly low in agriculture and industrial sectors compared to any other peer country.

the HRM

the HRM

For a society that has long taken immense pride in sending its labor force abroad to benefit from remittances, these are some daunting facts. In recent months, the country’s who’s who from political head honchos, policymakers, economists, private sector leaders, and prominent individuals of the society have sounded alarms regarding the exodus of young and working-age Nepalis. Never before has the migration of Nepalis, whether for overseas employment or education, raised such concern within the country.

For a society that has long taken immense pride in sending its labor force abroad to benefit from remittances, these are some daunting facts. In recent months, the country’s who’s who from political head honchos, policymakers, economists, private sector leaders, and prominent individuals of the society have sounded alarms regarding the exodus of young and working-age Nepalis. Never before has the migration of Nepalis, whether for overseas employment or education, raised such concern within the country.

This exodus of Nepal’s young workforce has serious consequences for the nation and its economy. Although politicians and policymakers now acknowledge that the harms of the departure outweigh the benefits that the country receives as remittance, the government has yet to fully assess the extent of the impact of the flight of human capital on the country’s economy.

Home to some 30 million people, Nepal features a predominantly youthful demographic, with almost 40 percent of the population belonging to the 15-39 age range. This age group is traditionally recognized as a crucial catalyst for economic progress in any nation, and Nepal is no exception. The country currently finds itself in a demographic advantageous position, reaping the benefits of a youthful population before the onset of aging and declining fertility rates over the next decade.

Home to some 30 million people, Nepal features a predominantly youthful demographic, with almost 40 percent of the population belonging to the 15-39 age range. This age group is traditionally recognized as a crucial catalyst for economic progress in any nation, and Nepal is no exception. The country currently finds itself in a demographic advantageous position, reaping the benefits of a youthful population before the onset of aging and declining fertility rates over the next decade.

A study conducted by HRM magazine reveals that Nepal has encountered challenges in capitalizing on the ‘demographic dividend’ inherent in its youthful populace. The term ‘demographic dividend’ refers to a society or country’s capacity to effectively utilize its young demographic for economic growth and wealth creation, before the population starts to grow old. This hurdle arises from a significant proportion of individuals aged 15 to 39 from all walks of life leaving Nepal in search of better opportunities elsewhere.

The converging factors of diminishing fertility rates – as pointed out by the National Population and Housing Census 2021- and the increasing migration of youths pose the risk of Nepal becoming a basket case of failed ‘demographic transition’ where the fertility rates decline with the greying of the population while income stagnates or decrease. Essentially, Nepal faces the challenge of ‘growing old without growing rich.’

The converging factors of diminishing fertility rates – as pointed out by the National Population and Housing Census 2021- and the increasing migration of youths pose the risk of Nepal becoming a basket case of failed ‘demographic transition’ where the fertility rates decline with the greying of the population while income stagnates or decrease. Essentially, Nepal faces the challenge of ‘growing old without growing rich.’

It is difficult to quantify the extent of the impact of out-of-country migration on different aspects of the economy. However, there are several sectoral trends and studies that have identified the impact of migration in these sectors and serve as points for reference for further discussions.

The Ever-increasing Youth Migration

The Tribhuvan International Airport in Kathmandu has become a testament to Nepal’s burgeoning youth migration phenomenon. On average, 2,500 individuals depart from the airport on a daily basis for higher education or employment opportunities. They come from all walks of life: skilled medical and nursing professionals, construction professionals and engineers, IT experts, students, hospitality professionals, bankers, sportspersons, semi and unskilled workers,

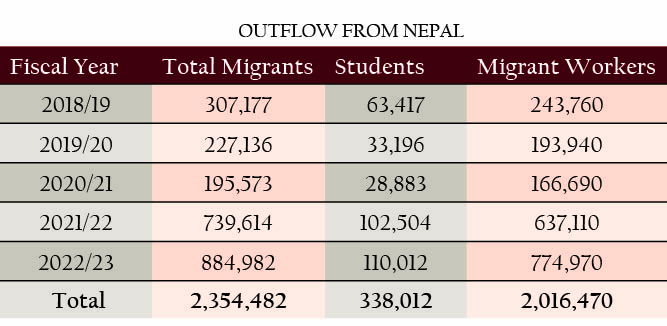

In the past half-decade, nearly 2.3 million Nepali citizens have migrated abroad. About 87 percent of these migrants were in pursuit of employment, while the remainder sought higher education opportunities abroad.

The migration trend has witnessed a significant upswing since the relaxation of COVID-19 pandemic-related travel constraints at the onset of the fiscal year 2021/2022. Specifically, in fiscal year 2022/2023, 884,982 individuals embarked on journeys abroad. Students accounted for 12 percent of this figure, while migrant laborers constituted the remaining 88 percent.

The surge in labor migration can be attributed to the resumption of labor mobility to Malaysia and the approval of new labor destinations in Europe and other parts of the world by the Government of Nepal. While Nepal has traditionally been a source of unskilled and semi-skilled labor migration for several years, the emerging trend of skilled professionals with several years of experience and youths departing immediately after completing their high school for higher study demands closer scrutiny. The mass exodus of qualified and fresh high school graduates carries multifaceted implications for the future of Nepali society.

The Remittance Quandary

The Remittance Quandary

Despite the immediate relief remittance income provides at the household level, it conceals several trends with long-term implications for Nepali society. Over the past two decades, migration from the hills to the Terai region and urban centers within the country has intensified, particularly among families receiving remittances from abroad. The direct consequence of this internal migration, supported by remittance income, has resulted in the neglect of arable land in rural areas. It has become difficult for those left behind in rural regions to find laborers for agricultural work, amplifying the workload for women, children, and senior citizens and jeopardizing their food security.

Since 2006, Nepal appears to be entangled in a cycle of dependency on remittances akin to the Dutch Disease phenomenon The import data reflects the consequences of youth migration, where the heightened inflow of remittances circulates back into the economy through the purchase of goods and services from foreign sources.Nepal finds itself in a conundrum—unable to halt youth migration and unable to provide opportunities within the country due to political and policy instability.

A substantial portion of remittance income is also directed to sending Nepali youth to foreign universities. While investing in human capital development is commendable, economists express concerns about the overall economic impact of this phenomenon. They argue that a significant portion of remittance money is funneled into sectors that do not directly contribute to Nepal’s economic development, leading to the concept of Nepal being trapped in a “remittance trap.”

The term “remittance trap” encapsulates Nepal’s dilemma—a heavy reliance on remittances as a significant income source, coupled with the challenge of bringing back skilled citizens studying abroad due to limited job opportunities within the country. The absence of job prospects and economic opportunities at home propels the Nepali workforce to migrate overseas for better employment prospects, perpetuating the cycle.

The term “remittance trap” encapsulates Nepal’s dilemma—a heavy reliance on remittances as a significant income source, coupled with the challenge of bringing back skilled citizens studying abroad due to limited job opportunities within the country. The absence of job prospects and economic opportunities at home propels the Nepali workforce to migrate overseas for better employment prospects, perpetuating the cycle.

According to Prof. Dr. Govinda Raj Pokharel, former Vice Chair of the National Planning Commission, while remittances have undeniably improved the standard of living of many Nepalis and lifted them out of poverty, a troubling predicament has emerged. “Nepal finds itself caught in a dilemma—we can’t afford to stop sending our youth abroad, yet we also desperately need their talents for our own development,” he said.

A Multi-sectoral Impact

The extensive migration of Nepali youth abroad has left an indelible mark on the country’s overall productivity and self-reliance. As migration is a very dynamic phenomenon, the macro-economic and sectoral impact has been carefully analyzed either by the government or the civil society. However, putting together the trends that are emerging from different sectors and discussions with industry experts and economists helps to assess the impact on different sectors of the economy. The main impact of the out-of-country migration has been stagnant productivity at the macroeconomic level. Similarly, every industry feels the repercussions of outbound migration. Particularly, hospitality, healthcare, construction, IT industries, manufacturing, and higher education sectors are bearing the brunt of this trend.

A recent World Bank study underscores the stark labor productivity gap between Nepal and peer countries, particularly in agricultural and industrial sectors. Nepal lags behind other countries in terms of productivity in these sectors, and the study attributes this phenomenon to various factors, with large-scale emigration being a prominent one. The significant departure of workers results in a brain drain, as the country loses its most talented workforce to foreign markets. This, in turn, can lead to a shortage of skilled labor domestically, stifling the growth of labor productivity, the study says.

A telling example of the escalating labor migration is evident in the surge of agricultural imports from India over the last two decades. Approximately 20 years ago, Nepal’s annual agricultural imports were a modest USD 11 million. Today, this figure has skyrocketed, surpassing USD three billion. This drastic surge in agricultural imports underscores a concerning reliance on foreign sources for essential food and agricultural commodities, undermining the self-sufficiency Nepal once boasted in this sector.

The ramifications of this trend are manifold. It not only strains Nepal’s trade balance by escalating the import bill but also renders the country susceptible to external market fluctuations and disruptions in the supply chain, putting vulnerable populations such as women, children, and older adults at risk of food insecurity. Additionally, the decline in domestic production adversely impacts the livelihoods of local farmers and the overall rural economy, warn economists.

In the hospitality sector, hotels and restaurants find skilled personnel for kitchen, food and beverage, and housekeeping roles increasingly challenging. Binayak Shah, President of Hotel Association Nepal (HAN), notes that trained professionals often seek better-paying opportunities abroad after gaining experience in Nepal. An HR manager at a star hotel in Kathmandu said that the management of many hotels often lack trust in Nepali chefs, opting to hire Indian chefs instead. This preference for foreign talent has led to domestic chefs seeking opportunities in Gulf countries due to frustration and a need for more local prospects.

In the hospitality sector, hotels and restaurants find skilled personnel for kitchen, food and beverage, and housekeeping roles increasingly challenging. Binayak Shah, President of Hotel Association Nepal (HAN), notes that trained professionals often seek better-paying opportunities abroad after gaining experience in Nepal. An HR manager at a star hotel in Kathmandu said that the management of many hotels often lack trust in Nepali chefs, opting to hire Indian chefs instead. This preference for foreign talent has led to domestic chefs seeking opportunities in Gulf countries due to frustration and a need for more local prospects.

The healthcare sector, encompassing medical doctors and nurses, also feels the strain from increased outward migration. The Nepal Medical Council data reveals a significant rise, with around 2,000 doctors obtaining permission to work abroad, compared to 1,320 in 2021. The government’s reluctance to open vacancies for doctors has further fueled this trend, with medical professionals seeking better opportunities abroad due to the scarcity of positions in Nepal.

Nurses, crucial to healthcare delivery, are leaving for countries like Australia and Israel exacerbating the understaffing of local healthcare institutions. Compounding the issue, the Nepal government has agreed to send 10,000 nurses to the United Kingdom over the next 10 years which will further deplete the healthcare workforce in the country.

In engineering and construction, skilled workers such as project managers, engineers, and laborers are migrating in large numbers. This migration has resulted in ongoing projects needing more staff, causing delays in critical infrastructure development. Over 60 percent of Nepali engineers have chosen to seek opportunities abroad, impacting the nation’s capacity to construct and maintain essential infrastructure.

IT is also another sector badly affected by the brain drain as professionals are drawn to opportunities in various countries. This has led to a shortage of skilled IT workers, hindering the growth of Nepal’s technology industry and its ability to compete globally.

Fresh graduates are succumbing to this trend, leaving Nepal for further studies abroad, often with no intention of returning. This brain drain has created a significant gap in the local talent pool, posing challenges for businesses and industries in finding innovative minds to drive growth and development.

“As youths depart, Nepal has been compelled to import a substantial number of laborers from India to meet the workforce demand in the market. While we benefit from remittances, a considerable portion of these earnings also flows out of the country,” warns Prof. Dr. Pokharel.

Investment in Higher Education is in Danger

As the number of students leaving the country for education abroad continues to rise, domestic higher education institutions are facing a challenge in filling their allotted admission slots. This trend poses a significant threat to the future of Nepal’s higher education system and jeopardizes the substantial private investments, amounting to billions of dollars, in the sector. According to the University Grants Commission (UGC), this decline is especially noticeable in institutions such as Tribhuvan University, Midwestern University, and Far Western University, raising serious concerns about the sustainability of these educational institutions.

Education entrepreneurs say there has been a 30-40 percent decline in student enrollment across colleges in the last two years. In the past year, a total of 182,900 students successfully completed their Plus Two education. However, the number of students who chose to pursue higher education in Nepali universities was significantly lower, with only 50,000 students enrolling. In the last two years, there has been a substantial 50 percent decline in student enrollment in colleges.

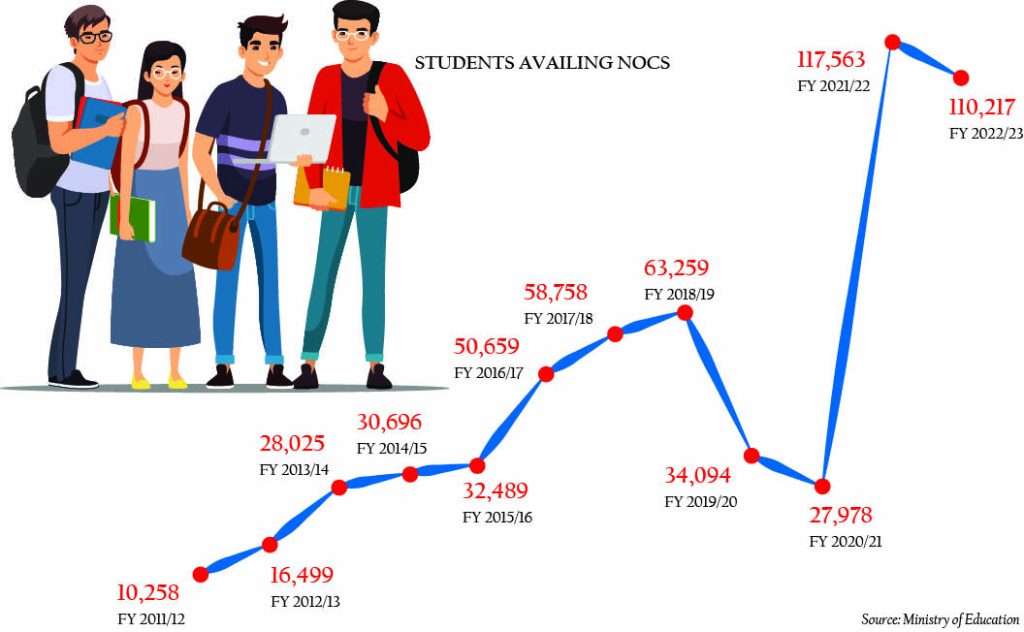

Recent data from the Ministry of Education underscores the growing trend of post-high school emigration. Approximately 600 students apply for a No Objection Certificate (NOC) from the ministry every working day, a prerequisite for Nepali students seeking foreign currency to finance their overseas higher education. In 2022 alone, a staggering 121,000 students obtained NOCs, a substantial increase from the previous year when 44,800 students received such approval.

The private college promoters attribute this decline to multiple factors, including the excessive politicization of education and the absence of a well-defined academic calendar within Nepali universities. “Our universities have struggled to attract students due to their inadequate infrastructure, lack of international-standard curricula, and ineffective teaching methods,” said Ramesh Silwal, President of the Higher Institutions and Secondary Schools’ Association Nepal (HISSAN). “Unfortunately, our government and political leadership have failed to instill confidence in our students that pursuing education within the country can secure their future,” he said. He added the trend of sending children overseas for education has gained prominence as a matter of social prestige among parents.

The private college promoters attribute this decline to multiple factors, including the excessive politicization of education and the absence of a well-defined academic calendar within Nepali universities. “Our universities have struggled to attract students due to their inadequate infrastructure, lack of international-standard curricula, and ineffective teaching methods,” said Ramesh Silwal, President of the Higher Institutions and Secondary Schools’ Association Nepal (HISSAN). “Unfortunately, our government and political leadership have failed to instill confidence in our students that pursuing education within the country can secure their future,” he said. He added the trend of sending children overseas for education has gained prominence as a matter of social prestige among parents.

Currently, there are a total of 1,432 colleges in the country, of which 63 colleges have not renewed their affiliation with Tribhuvan University. Additionally, there are over 1,500 education consultancies operating in Nepal. According to Silwal, there are 12,000 available seats for engineering education in Nepal, yet only 7,000 students have enrolled in these programs.

“This disparity between the number of seats and student enrollment poses a significant risk to the substantial investments made by the private sector in the education industry, which amounts to approximately Rs 700 billion,” said Silwal.

Economist Keshav Acharya finds these numbers startling and observes an upward trajectory. “Even more concerning, these young individuals show little inclination to return to Nepal, as they have lost hope in the government,” he said.

Echoing Acharya’s sentiments, Prof. Dr. Pushkar Bajracharya attributes a significant part of the issue to the government’s inability to instill hope and confidence in its citizens. He predicts a rise in emigration numbers in the years ahead.

According to Prof. Dr. Mahanada Chalise, one of the main reasons for many youths not to opt for higher education in Nepali universities is the country’s perceived lack of employment opportunities. “Even after completing their master’s degrees, graduates often struggle to find decent jobs, typically earning meager monthly salaries of around Rs 18,000-20,000. This situation is disheartening and discouraging for aspiring students,” he remarked.

Prof. Dr. Chalise is of the view that the domestic education system in Nepal faces criticism for its academic challenges. Cumbersome syllabi, a burdensome examination process, and delays in result publication discourage students from pursuing higher education within the country. “These issues contribute to losing interest in national universities and prompt many students to seek more favorable academic environments abroad,” he said.

Experts stress the need for more practical experience and work opportunities alongside academic studies in Nepal’s educational landscape. The absence of a “learn and earn” approach restricts students’ employability and readiness for the job market, further dissuading them from staying in the country for higher education, they say.

The Nepali Labor Market Paradox

Nepal grapples with a paradoxical situation in its labor landscape. In response to the absence of human resources caused by escalating labor outmigration, the country actively embraces a significant influx of skilled workers from abroad to meet the growing job demands within its borders.

The Nepal Labor Force Survey delineates the magnitude of this migration phenomenon. In 2008, Nepal boasted a workforce of 10.8 million individuals, a number that dwindled to seven million by 2018, underscoring the substantial migration of Nepali workers to foreign countries. This decline highlights the government’s challenge in creating new opportunities domestically. Prof. Dr. Bajracharya notes, “This data illustrates how the Indian labor force has come to dominate the Nepali market, fulfilling the job demand.”

A prime example of this dynamic is importing skilled workers from neighboring India. Nepal actively recruits masons, carpenters, tailors, and other professionals from across the border to address the skills gap in the domestic job market. This practice extends to the hospitality sector, where a significant proportion of Nepal’s hotels employ chefs from India to meet the culinary demands of the tourism industry.

“A staggering 1.2 million Indians and Bangladeshis are employed in Nepal. The annual remittances Nepal receives are nearly equivalent to those of Indian workers sent home from Nepal. In large industries, approximately 90 percent of the workforce consists of Indian laborers, with figures standing at 60 percent for medium-sized and 10 percent for small-sized industries. Nepal has failed to encourage its youth to participate in domestic industries, missing out on an opportunity to retain substantial amounts of foreign currency currently flowing to India,” said Prof. Dr. Bajracharya.

Kewal Prasad Bhandari, Secretary of Ministry of Labor, Employment, and Social Security, says that dependence on foreign labor is growing across various sectors of the Nepali economy. “Over 7,500 plumbers from the Indian state of Orissa are working in the Kathmandu Valley. Additionally, there is a growing demand for Indian artisans in the jewelry sector. Beyond India, even Bangladeshi workers have been enlisted to fulfill the needs of Nepal’s furniture-related industries,” he stated during a program in Kathmandu.

This intricate interplay between the export of Nepali labor and the import of foreign skilled workers highlights the unique labor dynamics unfolding in Nepal. It mirrors the country’s opportunities and challenges in managing its workforce, ensuring the domestic job market remains adequately staffed while its citizens pursue employment opportunities abroad.

Nepal’s Development Clock Ticking Away

Nepal’s Development Clock Ticking Away

The initial findings of the National Population and Housing Census 2021 have revealed stark realities for Nepal, which has long prided itself on its youthful demographic. The data discloses that Nepal’s population has been growing at an average rate of merely 0.93 percent, representing the slowest growth in 80 years.

These statistics unveil an unsettling trajectory for Nepal’s demographic structure, indicating that the country may no longer be able to boast of a youthful population in the next two and a half decades. The urgency lies in the fact that the current growth rate, now less than one percent, demands immediate action to leverage the potential of the nation’s youth for development and prosperity. In the coming decades, Nepal will grapple with significant strain on its resources, meeting the healthcare and allowances required for an aging population.

“Nepal’s population is rapidly aging, with a growth rate of less than one percent, resulting in a shortage of young labor. Meanwhile, the burden of social security continues to mount year after year,” cautioned Prof. Dr. Pokharel.

Compounding the issue is the allure of developed countries, drawing talented youths away. Thus, there is an imperative for Nepal to create enticing opportunities domestically to stem the mass migration of its youth abroad. Official data exposes a high unemployment rate in Nepal, standing at 11.4 percent, with the youth aged 15-24 and 25-34 experiencing the highest unemployment rates. According to experts, this persistent unemployment is propelling the active population to seek more promising prospects elsewhere, leaving the country’s economy in a vulnerable state.

“Not only are we losing our youth, but we are losing essential human capital crucial for development. Individuals working in the Middle East and Malaysia are sending their children to Western countries for education, which could result in these individuals returning to Nepal in old age, necessitating significant healthcare resources without contributing significantly to the economy,” said Acharya, adding, “This trend poses a threat to economic growth and development in Nepal. We anticipate an aging population in the not-so-distant future.”

Almost half a million young individuals enter Nepal’s job market annually, and a substantial portion choose to migrate abroad in search of better opportunities. Consequently, Nepal finds itself in a race against time for development, with a considerable chunk of its youth population abroad, traditionally the driving force for progress. If unchecked, this trend could pose substantial challenges in the next two to three decades as Nepal’s population ages. Therefore, swift and strategic action is imperative for the nation to harness its youth potential and ensure sustainable development.

The Need for Considerate Measures

Economists stress that while a potential solution exists, it is undeniably formidable. “Effectively addressing these intricate issues demands a concerted effort from both the government and the private sector to direct remittances into productive sectors and establish sustainable opportunities for the youth. However, the government must demonstrate genuine commitment. Creating job opportunities through remittances presents a significant potential,” said Acharya. Countries like Japan, South Korea, and Malaysia have encountered comparable challenges of youth migration, but they have proactively implemented measures to tackle the crisis and devised policies geared towards achieving economic development and prosperity.”

According to Prof. Dr. Pokharel, Nepal urgently needs policies mandating vocational training for youths seeking foreign employment to tackle these challenges. “Providing youths with training will enhance their earning potential abroad and enable them to return to Nepal and contribute to our society. Policy-level changes are crucial to alleviate the issue of mass emigration from Nepal, given the alarming current numbers, putting the nation’s future at risk,” he opined.

According to Prof. Dr. Bajracharya, the remittance inflow to Nepal amounts to approximately Rs 1,400 billion annually, and when considering informal channels, this figure may reach Rs 2,400 billion. “Even if a small portion of these remittances were used for capital formation, it could yield substantial benefits in the future,” he noted.