Nepal’s energy sector has achieved a significant milestone over the last decade, particularly within the hydropower industry. Tangible results have been garnered from continuous sectoral reforms, steering the country toward a stable growth trajectory. Despite the adversities of political unrest and frequent natural disasters, Nepal maintained a BB- rating in 2025 due to the progress achieved in its energy infrastructure.

Nepal’s energy sector has achieved a significant milestone over the last decade, particularly within the hydropower industry. Tangible results have been garnered from continuous sectoral reforms, steering the country toward a stable growth trajectory. Despite the adversities of political unrest and frequent natural disasters, Nepal maintained a BB- rating in 2025 due to the progress achieved in its energy infrastructure.

“Nepal’s medium-term growth prospects will be supported by continued investment in hydropower generation and transmission, more reliable electricity supply, and structural reforms to improve the business climate, boost productivity and create jobs,” Fitch Ratings underlines in its Sovereign Country Rating Report.

“Nepal’s medium-term growth prospects will be supported by continued investment in hydropower generation and transmission, more reliable electricity supply, and structural reforms to improve the business climate, boost productivity and create jobs,” Fitch Ratings underlines in its Sovereign Country Rating Report.

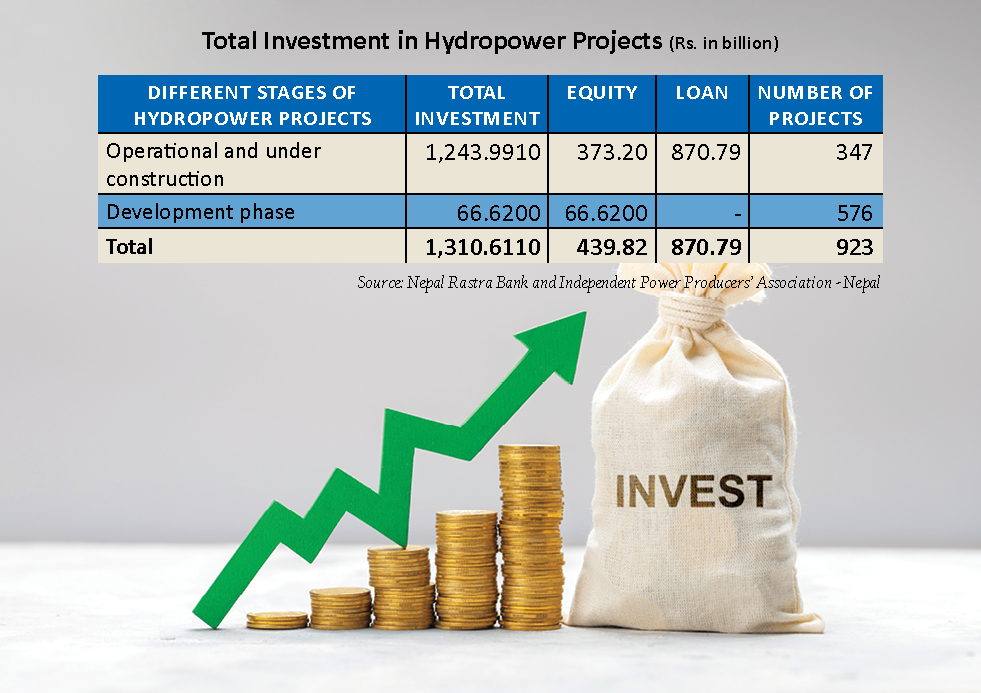

Undoubtedly, there has been significant investment in this field. Currently, there are over 347 hydroelectric projects totalling 7,251 megawatts – 2,948 MW operational and 4,303 MW under construction – and the government recently unveiled an Energy Development Roadmap envisioning 28,500 MW by 2035.

Independent power producers have invested Rs. 1,243.99 billion into the sector. Around 67.5% of this capital is sourced from banks and financial institutions (BFIs). Furthermore, hydropower companies have issued public shares, contributing significantly to the development of the country’s capital market.

Market assurance lures private investment

Nepal’s transformation from an energy-starved nation to a net power exporter within a decade is anchored by its Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) policy, governed by the Electricity Act of 1992. This policy has provided market assurance and secured returns for private investors. Consequently, independent power producers have not only invested heavily in energy generation but are now also eager to fund transmission infrastructure and engage in cross-border power trading.

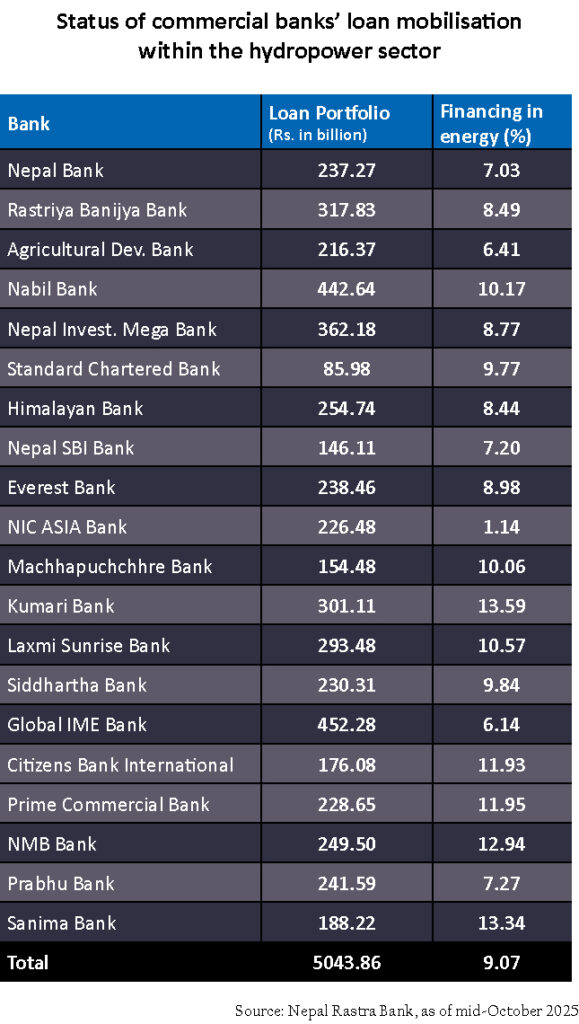

The power purchase agreements with the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) – the country’s sole power off-taker – have enhanced the creditworthiness of projects, serving as reliable collateral for banks and financial institutions. Moreover, the Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB) has directed commercial banks to allocate 10% of their total loan portfolios to the energy sector, significantly augmenting bank investment. As of mid-October, commercial banks have reached a 9.07% allocation in the energy sector, largely abiding by the central bank’s directed lending policy.

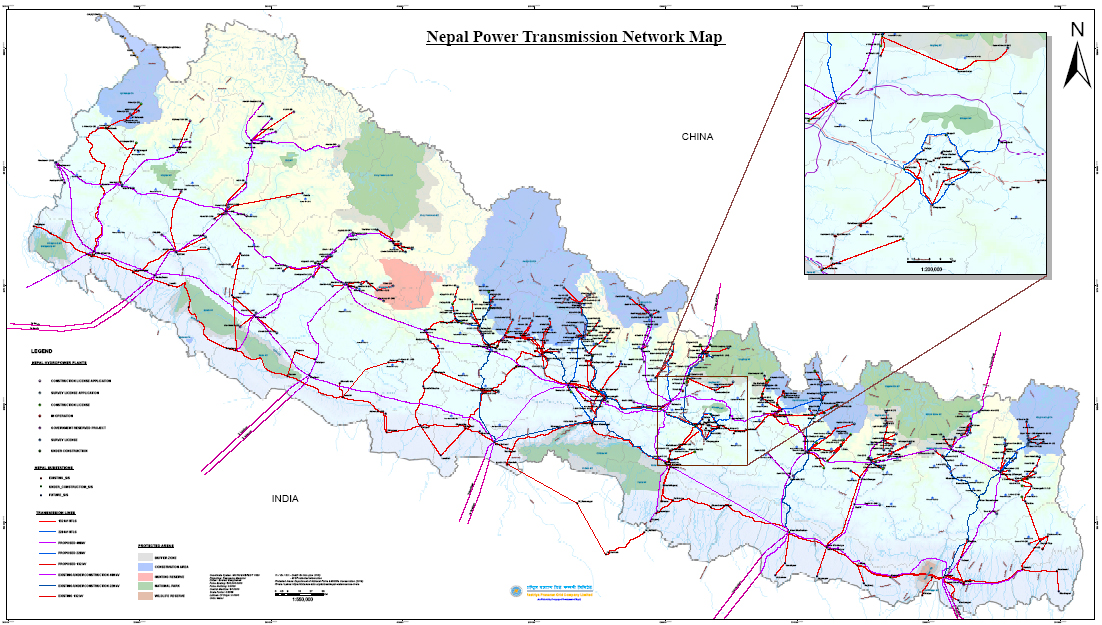

The landmark deal with neighbouring India to export 10,000 megawatts over 10 years has expanded the market for Nepal’s electricity, luring more foreign investment into the sector. In the initial year of this agreement, Nepal exported approximately 1,140 megawatts of surplus energy to the Indian market. Over the years, Nepal has developed robust transmission infrastructure and strengthened distribution networks, including feeders and cables, which has enhanced the quality and reliability of the electricity supply while providing access to 99% of households.

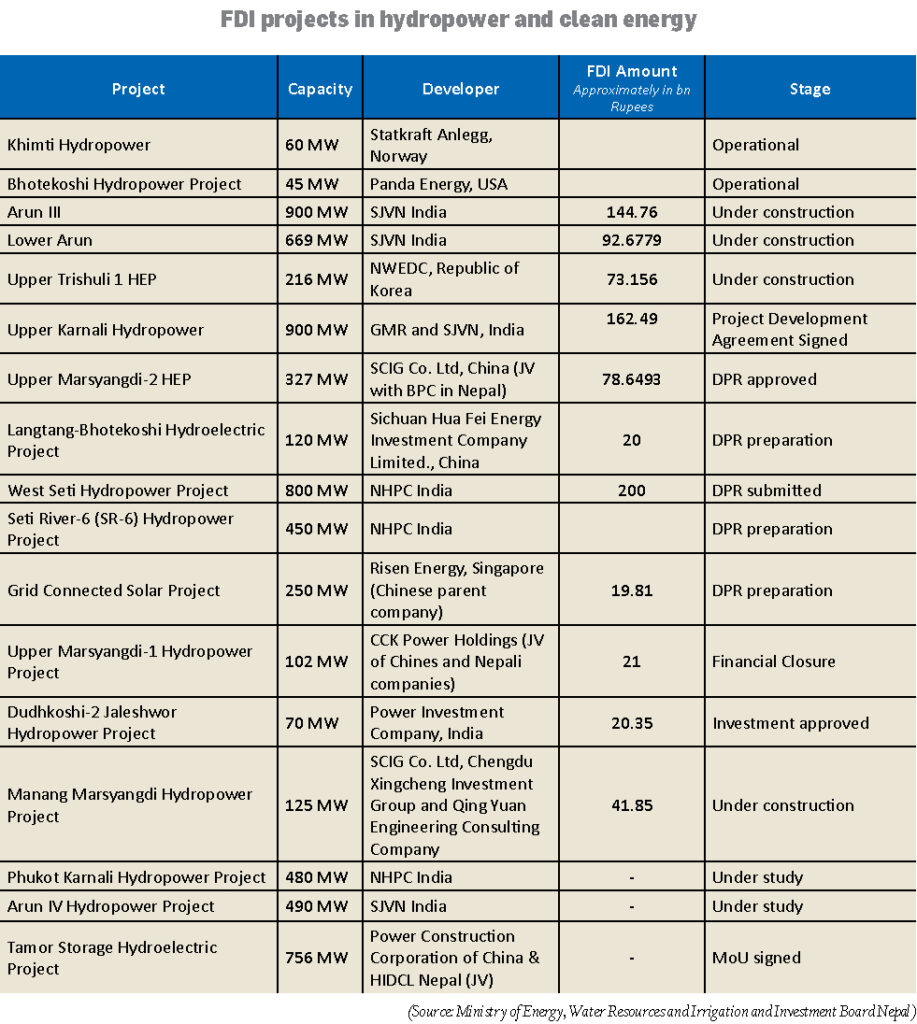

Nearly fifteen years after the two major foreign investment projects in hydropower generation, the 60 MW Khimti Hydropower by the Norwegian company Statkraft Anlegg and the US-based Panda Energy’s investment in the 45 MW Bhotekoshi Hydroelectric Project, the country has welcomed FDI in more than a dozen new projects. These range from the 102-megawatt Upper Marsyangdi-1 HEP to the massive 900-megawatt Arun III hydropower project.

Industrial benefits

Hydropower projects are both cost and labour-intensive, generating significant employment alongside industrial benefits for suppliers of construction materials. As numerous hydropower projects are constructed simultaneously, this synergy could help increase aggregate demand, according to Pashupati Murarka, owner of the Murarka Organisation.

Construction material production industries have thrived in Nepal. However, demand has plummeted over the last few years due to a slowdown in government-led construction activities. Industrialists remain upbeat that demand could pick up once the construction of large-scale hydropower projects gathers pace.

Creating conducive environment

Creating conducive environment

However, policy inconsistency has been hindering investment. Particularly regarding PPAs, the government frequently changes its stance between “take or pay” and “take and pay” agreements. Considering Nepal’s suppressed power demand, a “take and pay” PPA fails to assure the market because it is conditional, whereby the off-taker is only obliged to pay if they actually take the power, leaving the investor to bear the sole risk. According to IPPs, moving away from “take or pay” models could deter future investments.

Conversely, the Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) states that the entity is focusing on addressing power deficits primarily during the winter, which requires peaking and storage or reservoir projects. Snow-fed run-of-the-river projects produce only about one-third of their rated capacity during the winter as river levels drop.

“Despite having surplus power in the wet season, we’ve been compelled to import power from India during the dry season. The mismatch in demand and supply in the dry season will continue for a few more years,” said Hitendra Dev Shakya, Managing Director of the NEA. “Our priority is storage projects, including pump storage and battery storage, to enhance stable power generation.”

Ganesh Karki, President of the Independent Power Producers’ Association – Nepal (IPPAN), has stated that the government should introduce a sunset law to execute the Energy Development Roadmap of 2025. “If we fail to exploit our hydropower potential within a decade, its relevance may vanish amid changing dynamics such as the rise of hydrogen energy and the increasing threats of climate-induced disasters, which could build pressure against constructing large-scale reservoir projects,” he states.

Karki adds, “To fully exploit Nepal’s hydropower potential, the government should declare an ‘electricity emergency decade’ or an ‘electricity development decade.’ Implementing a sunset law for at least 10 years would streamline all relevant regulations. Under this law, both the government and the private sector would work collaboratively in mission mode to accelerate project development.”

Karki adds, “To fully exploit Nepal’s hydropower potential, the government should declare an ‘electricity emergency decade’ or an ‘electricity development decade.’ Implementing a sunset law for at least 10 years would streamline all relevant regulations. Under this law, both the government and the private sector would work collaboratively in mission mode to accelerate project development.”

Energy security and composition of energy consumption

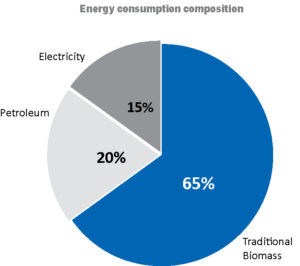

Energy security is crucial for any nation, as energy consumption serves as a key indicator of a country’s economic status. Currently, Nepal’s per capita energy consumption remains low within the South Asian context. However, it reached 380–400 kWh per year as of 2023–2024, representing a significant increase compared to the 150 kWh recorded in 2015/16.

Electricity currently contributes the least to the national energy basket. To achieve Nepal’s aspiration of ‘Sustainable Energy for All’ by 2030, in line with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the country has immense potential to substitute traditional biomass or high-emission sources with clean energy. Peak power demand presently stands at 1,650 MW.

“Clean cooking solutions and electric transport can not only increase electricity demand but also boost per capita energy consumption. If the Nepal Electricity Authority can supply more, demand will certainly rise within the industrial sector as well,” explains energy specialist Gyanendra Lal Pradhan.

According to the NEA, the domestic sector was the primary consumer of electricity, accounting for 42.12% of total usage in FY 2023/24, while the industrial sector consumed 36.12%. Commercial users accounted for 8.08%, non-commercial for 3.15%, and other sectors for 10.51%. Regarding the customer base, 95.54% are domestic users, followed by industrial (1.26%), commercial (0.75%), non-commercial (0.71%), and other categories (5.73%).

Concerns over NEA’s financial health

Concerns over NEA’s financial health

Hydropower experts are concerned about the financial health of the Nepal Electricity Authority, the sole power off-taker, while it signs PPAs without first stimulating domestic power demand. “The numbers game regarding megawatts doesn’t matter. This is merely a political gimmick. The political leadership wishes to create an impression by showcasing high megawatt figures, but our focus should be on advancing strategic projects,” according to Radhesh Pant, Former CEO of Investment Board Nepal. “This will require institutional reforms, cost-reflective tariffs, and new PPA structures and mechanisms to reduce the financial burden on the NEA.”

He advised implementing open access to develop a multi-buyer and multi-seller electricity market domestically. This would reduce the dominance of and burden on a single entity, while creating a framework that allows the private sector to participate in electricity trading and the development of transmission lines.

Transmission and power trade

Nepal has significantly expanded its transmission network and cross-border power trading infrastructure over the last decade. Alongside major high-capacity lines like Dhalkebar-Muzaffarpur (currently operational) and New Butwal-Gorakhpur (under implementation via Millennium Challenge Corporation grant assistance), the 217-km, 400 kV Arun III cross-border line – running from the powerhouse to Sitamarhi, India, via Mahottari – serves as an integral component of the Arun III project.

Several other points are utilised for cross-border trade with India. However, these three major lines are the building blocks for long-term power trade, potentially unlocking regional potential. Furthermore, the Lamki-Bareli cross-border line may soon be developed to transmit power evacuated from projects in the West-Seti Corridor.

In tandem with these developments, the government has opened the transmission sector to private investment, as state funding is insufficient to execute the transmission master plan. Provisions for infrastructure sharing have also been introduced, paving the way for private involvement in power trading. However, since independent power producers have already agreed to sell their power to the NEA, the NEA remains the sole entity currently involved in cross-border power trading.

“Among the four major components of the energy sector, which include generation, transmission, distribution and power trade, generation and power trade can be market-driven. However, we must foster a conducive environment for private investment. We are currently developing guidelines for open access and transmission usage charges, similar to how private vehicles pay fees to use public highways,” says Ram Prasad Dhital, Chairperson of the Electricity Regulatory Commission.

“This arrangement will allow private power generation projects to sell electricity directly to industries by paying a designated fee to the Nepal Electricity Authority for the use of their transmission lines. Producers could also split their sales between the NEA and other industrial consumers. This shift will end the NEA’s market monopoly, foster competition, and eventually lead to a fully competitive energy market,” shares Dhital.

Way forward

Nepal has proven to be a successful implementer of the public-private partnership (PPP) model, leveraging private sector investment primarily in small and mid-scale projects. While the 900 MW Arun III stands as a major large-scale FDI project, further energy sector reforms could provide the necessary momentum for other strategic projects essential to unlocking the country’s potential.

Key among these is Budhi Gandaki (1,200 MW), which requires an investment of Rs. 400 billion, in addition to the Rs. 45 billion already spent on land compensation and preparatory works. Meanwhile, the 635 MW Dudhkoshi project is progressing with a financing commitment from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), though de-risking models and other preparations remain underway.

Key among these is Budhi Gandaki (1,200 MW), which requires an investment of Rs. 400 billion, in addition to the Rs. 45 billion already spent on land compensation and preparatory works. Meanwhile, the 635 MW Dudhkoshi project is progressing with a financing commitment from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), though de-risking models and other preparations remain underway.

West Seti and SR-6, with a combined capacity of 1,200 MW, remain in a stalemate, even though NHPC India has submitted the Detailed Project Report (DPR) for West Seti to the Investment Board Nepal. Additionally, experts argue that the 1,063 MW Upper Arun, considered the “crown jewel” of Nepal’s hydropower resources, should be developed with special priority.

These projects are being advanced through a mix of domestic and foreign resources, both by the government and through foreign direct investment. Under the PPP modality, the risk-and-benefit-sharing approach between the state and developers is regarded as a successfully implemented model, as evidenced by the numerous projects completed to date.