Low-base effect fuels bank profit growth but challenges persist

Banks’ performance and dividend payouts gained traction in Fiscal Year 2024/25, alongside an improvement in credit expansion. Unlike the situation in 2023/24, which was marked by low credit growth and high provisioning requirements, banks and financial institutions (BFIs) recorded a strong profit last fiscal year, as shown in their unaudited financial statements. The significant increase in profit is largely due to the low-base effect from FY 2023/24.

In recent fiscal years, BFIs have faced unfavourable conditions because of sluggish loan demand. After a record-high credit growth of 27% in FY 2020/21, Nepal Rastra Bank – the country’s central regulatory and monetary authority – implemented strict measures on credit expansion. At the same time, Nepal’s foreign exchange reserves declined, and imports of luxury goods were restricted.

BFIs’ balance sheets were negatively impacted by the dual challenges of excess liquidity and slumping credit demand. However, their performance improved in FY 2024/25, thanks to a substantial expansion of credit to the private sector and the low-base effect of FY 2023/24. Furthermore, there are signs of improvement in credit mobilisation.

According to Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB), credit growth was 8.4% in FY 2024/25, compared to the previous fiscal year’s growth of just 5.6% – which was significantly lower than the 12.6% growth in deposits during the same period.

Credit expansion is essential for banks to generate income, as their primary business model involves borrowing to lend. Interest income is the main source of earnings for banks, though they also earn from various other sources, such as cards, digital banking services, investments in government securities, and foreign currency transactions.

Private sector credit expansion has propelled the economy, with a projected GDP growth of 4.8%. Although this growth is linear, it’s encouraging. According to Finance Secretary Ghanashyam

Upadhyaya, “Stagnation in investment from both public and private sectors in the recent past had a severe impact on growth and jobs.” The current monetary policy aims for a credit growth of 12.5% to achieve the desired economic growth of 6%.

Market scenario

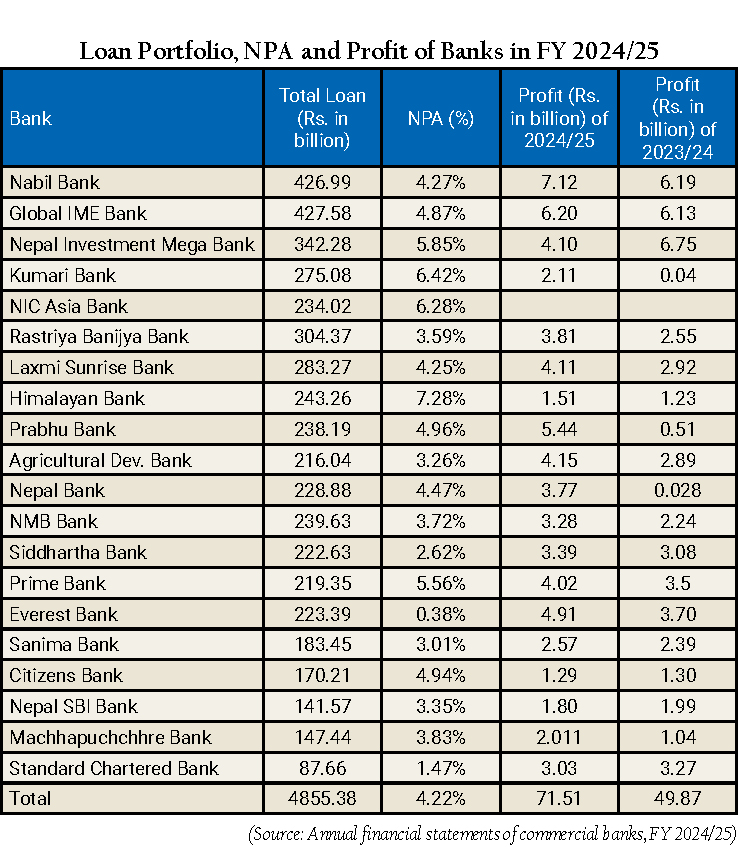

Commercial banks have mobilised deposits worth Rs. 6,443.71 billion against a total credit size of Rs. 4,855.38 billion. In the 2024/25 fiscal year, commercial banks earned Rs. 71.5 billion in profit, compared to Rs. 49.87 billion in the previous fiscal year. This significant profit growth is a result of the low-base effect from FY 2023/24.

The monetary policy has eased credit flow by offering flexible conditions, such as allowing non-banking assets to be counted as Tier 2 capital and permitting the issuance of perpetual shares to address commercial banks’ solvency concerns. According to Manoj Gyawali, CEO of Nabil Bank, “Banks and financial institutions are gradually building their portfolio. Although the monetary policy has provided flexibility for credit expansion to the private sector, their appetite is a major concern.”

The private sector has long blamed NRB for restricting credit expansion with its ‘Working Capital Guidelines’. This guideline, which took effect on October 18, 2022, was designed to crack down on the misuse of bank credit. It restricts credit to between 25% and 40% of a borrower’s annual transactions. For small borrowers with credit between Rs. 10 million and Rs. 20 million, the limit was 40%. The guideline requires borrowers with credit exceeding Rs. 50 million to submit quarterly financial statements certified by an independent auditor, while those with credit below Rs. 50 million must submit self-certified monthly statements.

To address private sector concerns, the central bank has eased credit mobilisation. The Monetary Policy 2024/25 initially suspended the enforcement of the Working Capital Guidelines from mid-July 2024 to mid-July 2025. However, Nepal Rastra Bank recently extended this grace period for another two years, until mid-July 2027, giving borrowers sufficient time to adjust their credit based on their annual turnover.

According to Anjan Shrestha, Senior Vice President of the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FNCCI), “The private sector has an appetite to invest, but investment climate reform is key to boosting their confidence.” A study by the FNCCI found that government spending has a multiplier effect on private sector investment; every rupee the government invests in development helps mobilise five rupees from the private sector.

On the other hand, there is an opposing view that large corporations are overfinanced and lack further appetite for bank credit. With the two-year extension of the Working Capital Guidelines, credit may be sought for businesses with a short payback period, such as trading.

Profit of commercial banks surges by 43.39%

Thanks to a low-base effect, commercial banks saw an exponential 43.39% surge in profit during Fiscal Year 2024/25. No commercial banks reported a loss this year. Nabil Bank was the top earner, with a profit of Rs. 7.12 billion, followed by Nepal Investment Mega Bank (Rs. 6.75 billion), Global IME Bank (Rs. 6.20 billion), Everest Bank (Rs. 4.91 billion), and Nepal Bank (Rs. 3.77 billion). Government-owned banks also performed astoundingly, with Nepal Bank ranking in the top five. The other two government-owned banks, Rastriya Banijya Bank and Agricultural Development Bank, recorded profits of Rs. 3.81 billion and Rs. 4.15 billion, respectively.

The bottom five banks in terms of profit were NIC Asia (Rs. 161.57 million), Citizens (Rs. 1.29 billion), Himalayan Bank (Rs. 1.51 billion), Nepal SBI Bank (Rs. 1.80 billion), and Machhapuchchhre Bank (Rs. 2.01 billion).

NPL shoots up

NPL shoots up

The non-performing loans (NPLs) of commercial banks have shot up to 4.22%, tripling in the last three years. Analysts believe the actual NPL figure is likely underreported and could be twice as high if loan restructuring and rescheduling facilities were not in place.

Considering the commercial banks’ total loan portfolio of Rs. 4,855.38 billion, the NPL is approximately Rs. 205 billion. Financial sector analyst Anal Raj Bhattarai stated, “The situation of NPL is already alarming, and there are still concerns about the asset quality of banks.”

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has repeatedly raised concerns about the asset quality of Nepal’s banks. The country has a history of recapitalising institutions like Nepal Bank and Rastriya Banijya Bank due to high NPLs. In the early 2000s, NPLs at Rastriya Banijya Bank were staggeringly high, reaching 60% or more.

Since credit growth has not been supporting GDP growth, there are concerns about the misuse of credit. As part of its Extended Credit Facility, the IMF has requested a review of the asset quality of 10 commercial banks by an internationally recognised independent audit firm. This process has already begun.

In Fiscal Year 2024/25, Himalayan Bank and Kumari Bank had the highest NPLs at 7.28% and 6.42%, respectively, followed by NIC Asia at 6.28%, and Nepal Investment Mega Bank and Prime both at 5.56%. Despite their large portfolios, Global IME Bank and Nabil Bank also have significant NPLs. Global IME Bank’s NPL is 4.87% with a loan portfolio of Rs. 427.58 billion, while Nabil Bank’s NPL is 4.27% with a portfolio of Rs. 426.99 billion.

Consequences of high NPL

High non-performing loans (NPLs) are a threat to depositors’ savings, as the money banks lend comes directly from them. This ultimately erodes public trust in banks and financial institutions. Additionally, high NPLs can prevent BFIs from paying dividends to their promoters and shareholders and reduce their capacity to lend, making the prudent operation of BFIs and financial sector stability essential.

Nepal Rastra Bank Governor Biswo Nath Poudel publicly stated that NPLs are high in the agriculture and other sectors where the central bank has a directed lending policy. This has sparked a debate on whether the central bank should continue with this policy. Furthermore, there are concerns about the central bank’s supervisory capacity and its ability to intervene in a timely manner.

Despite the soft measures introduced by the Monetary Policies of 2024/25 and 2025/26, banks’ NPLs remain high. The NRB has been accused of being too lenient with banks and boosting their profits by tweaking prudential norms, which could lead to a more alarming NPL situation.

Meanwhile, there is a lack of clarity regarding the operational model of the Assets Management Company (AMC). Although the central bank has reportedly drafted the AMC Bill and submitted it to the Ministry of Finance for parliamentary approval, some believe it won’t be effective. Kamalesh Kumar Agrawal, President of Nepal Chamber of Commerce, stated, “Without representation of the private sector in the AMC, the government alone cannot operate it transparently and prudently.”

Soft supervision and regulatory tweaks conceal NPL

In early Fiscal Year 2024/25, the central bank’s monetary policy revised the loan loss provisioning for loans in the pass category, lowering it from 1.20% to 1.10%. Additionally, the policy met bankers’ requests by allowing loans to be classified as ‘watchlist’ immediately upon the resumption of debt service. Previously, even if debt service resumed, a loan classified as a ‘loss’ remained in that category for six months, requiring a 100% provisioning. However, the new provision allows such a loan to be classified as a ‘watchlist’ loan immediately upon debt service resumption, which requires only 5% provisioning.

When debt service on a loss/bad loan becomes regular, it must be classified under the ‘watchlist’ category for six months before it can be reclassified as a pass/good loan. The ‘watchlist’ category requires only 5% loan loss provisioning.

Despite the attempts by the central bank and banks to conceal Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) through reclassification and deferred loan repayments (regulatory measures) and soft supervision, NPAs have been increasing significantly over time.

Bankers, however, justify that the current non-performing loan rate isn’t alarming, given how Nepal’s economy has been affected by global shocks. They argue that an NPL rate of 4.42% is not a cause for concern when considering the more than four decades of private banking in Nepal and the long history of state-owned banks.

Many believe that the reported figure significantly understates the actual non-performing asset situation. Loan ageing is a key factor in determining NPLs. A loan’s classification deteriorates based on how long repayments are stalled. A loan moves from the ‘pass’ category to the ‘watchlist’ if repayment is stalled for one to three months, requiring a 5% loan loss provisioning. If repayment stalls for three to six months, it is classified as ‘substandard’, requiring a 25% provisioning. If repayment is stalled for six to 12 months, it is classified as ‘doubtful’, and a 50% provisioning is required. After one year or more of stalled payments, the loan is classified as a ‘loss’ loan, which requires 100% provisioning.

Recovery challenges

The increasing number of non-performing assets has exposed the recovery challenges faced by banks and financial institutions. Adding to these risks, fiscal policy is encroaching on the domain of monetary policy. For the 2025/26 fiscal year, the government’s budget announced that it would provide restructuring and rescheduling facilities for borrowers severely affected by the economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent shocks.

According to experts, this type of fiscal policy, which is largely aimed at gaining popularity, significantly encroaches on the central bank’s authority to protect depositors’ money and build their confidence. Based on the direction of fiscal policy, the central bank has become too lenient with borrowers and has overlooked the protection of depositors, which could damage public trust in BFIs. It has also been reported that simply deferring loan repayments will only lead to a greater accumulation of problems.

Given this situation, the central bank must work on finding a lasting solution and make a conscious effort to prevent the potential fallout of being overly flexible with borrowers. This leniency ultimately poses recovery challenges for banks and threatens the stability of the entire financial sector.