Challenges and the Influence of Private Sector Practices

Human resource management (HRM) in the public sector is the most pressing issue and a central component of administrative reforms, ultimately driving broader impacts on governance. Over the years, Nepal has implemented various reform practices aimed at enhancing efficiency in public service delivery. This includes the adoption of private sector management practices, often categorised as ‘hard approaches’, such as performance evaluation and reward and compensation (e.g., result-based incentives in limited sectors).

Human resource management (HRM) in the public sector is the most pressing issue and a central component of administrative reforms, ultimately driving broader impacts on governance. Over the years, Nepal has implemented various reform practices aimed at enhancing efficiency in public service delivery. This includes the adoption of private sector management practices, often categorised as ‘hard approaches’, such as performance evaluation and reward and compensation (e.g., result-based incentives in limited sectors).

While the public sector is advancing its HRM capabilities by incorporating core functions, it still lags significantly behind the private sector due to several factors. Fundamentally, initiating change within the government system is inherently more complex than in the private sphere.

Nevertheless, as noted by Bimal Prasad Wagle, Former Secretary of the Government of Nepal, it is widely accepted that public corporations, state-owned enterprises (SoEs), regulatory bodies, and investment promotion agencies, collectively viewed as the commercial face of the government, should exhibit greater flexibility and agility in adopting efficient management practices.

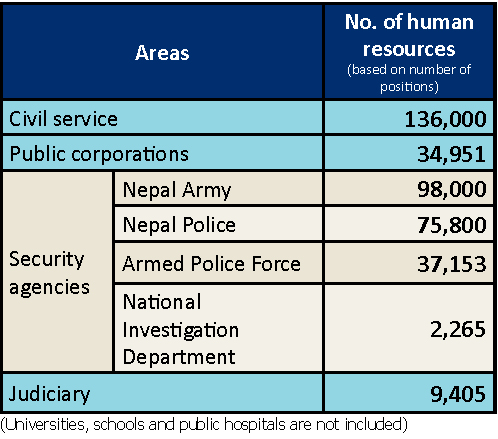

Wagle mentions, “The aforesaid sectors can play a pivotal role in transferring knowledge and human resource management practices to the rest of the public sector.” This broader public sector encompasses the full spectrum of state organs like the executive, legislature, and judiciary. More specifically, this includes the three tiers of government, parliament, judiciary, constitutional bodies, independent commissions, security forces, public schools and universities, public hospitals, and government-owned non-banking financial institutions, such as the Employees Provident Fund, Citizen Investment Trust, and Social Security Fund, among others.

Wagle mentions, “The aforesaid sectors can play a pivotal role in transferring knowledge and human resource management practices to the rest of the public sector.” This broader public sector encompasses the full spectrum of state organs like the executive, legislature, and judiciary. More specifically, this includes the three tiers of government, parliament, judiciary, constitutional bodies, independent commissions, security forces, public schools and universities, public hospitals, and government-owned non-banking financial institutions, such as the Employees Provident Fund, Citizen Investment Trust, and Social Security Fund, among others.

Against this backdrop, the government recently introduced a corporate governance policy for state-owned enterprises (SoEs), which specifically emphasised the execution of modern Human Resource Management (HRM) practices to maximise growth.

Initially, during authoritarian rule, bureaucrats were appointed directly by the ruler, owing their loyalty to that leader and serving to achieve the objectives set by their command. Subsequent upheaval in the bureaucracy, often accompanying a change in leadership, resulted in a lack of institutional memory and accountability. The progressive democratisation in thought processes over the years eventually led to a critical debate regarding the stability of the bureaucracy.

The modern form of bureaucracy, characterised by a hierarchy of authority, rule-based management, division of work based on expertise, and employment based on qualifications, was first introduced after the 1920s. Following this, the introduction of New Public Administration in the late 1960s shifted the focus of public administration towards social equity and responsiveness to public needs. The most prevalent of current civil service trends, New Public Management (NPM), emerged after the 1980s, injecting private sector management practices into the public sector.

The concept of New Public Management fundamentally steers the government to provide strategic guidance, establish the rules of the game, regulate, and open up public goods and services delivery to the private and non-governmental sectors while safeguarding consumer interests. This represents a major shift away from the traditional concept that the government should handle everything, from the supply of public goods and services to infrastructure development.

Concurrent with the political change of 1990, Nepal enacted significant legal, administrative, and procedural reforms. These changes opened up private sector investment for public goods and services, and strengthened the regulatory system to ensure a level playing field for the private sector as well as robust consumer protection. The former concept of a ‘rowing government’, characterised by the government’s pervasive presence and intervention, has been altered.

This landmark reform initially led to the development of professionalism in the civil service, but this progress was later undermined by the over-politicisation of the bureaucracy, which ultimately killed the spirit of the reform. “If the spirit of reforms were carried out rightly, the government would be enabled with the capacity to perform better and deliver accordingly to meet public satisfaction,” states Mahesh Acharya, Former Finance Minister, who was a key figure in leading these reform initiatives in the 1990s.

This landmark reform initially led to the development of professionalism in the civil service, but this progress was later undermined by the over-politicisation of the bureaucracy, which ultimately killed the spirit of the reform. “If the spirit of reforms were carried out rightly, the government would be enabled with the capacity to perform better and deliver accordingly to meet public satisfaction,” states Mahesh Acharya, Former Finance Minister, who was a key figure in leading these reform initiatives in the 1990s.

Lack of proper job evaluation

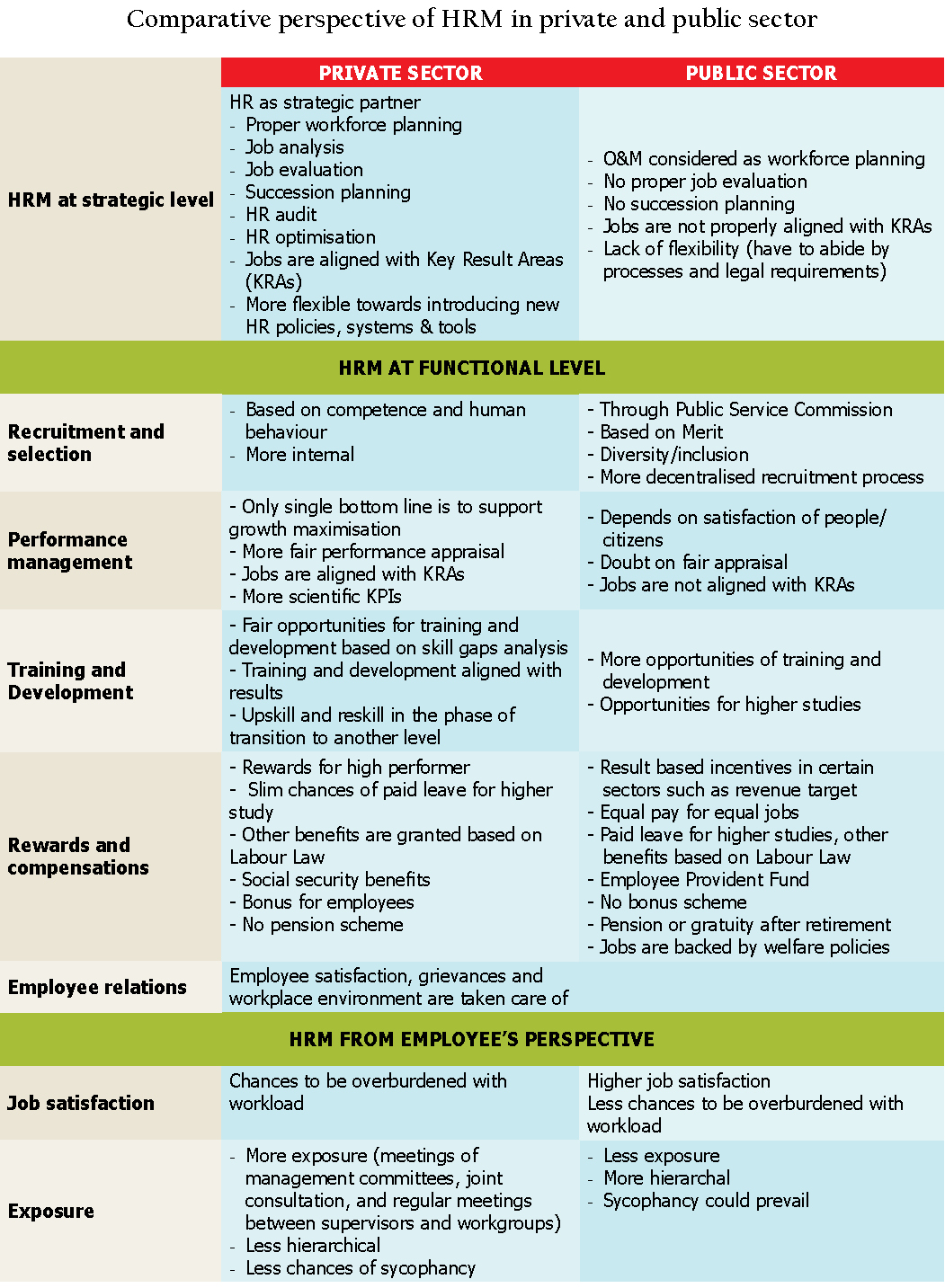

The New Public Management (NPM) has introduced private sector management functions into the public sector. However, questions regarding the effectiveness of these functions remain. Moving forward, the private sector has already acknowledged Human Resources (HR) as a strategic partner, a concept that represents a fundamental gap in the public sector. In the private sector, HR has been gradually accepted as a strategic partner, and their involvement in key decision-making begins with workforce planning.

In the government, the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration (MoFAGA) is officially assigned strategic HR planning in the civil service, with an administration division in each ministry and public institution to conduct HR functions. Nevertheless, HRM in the public sector needs to be better streamlined with key result areas. Even the Organisation and Management (O&M) surveys are not conducted scientifically, and authorities have frequently been flagged for the distortion found in O&M reports. Since the O&M report must be approved by the Cabinet, its approval process often depends on influence and power.

For instance, Former Foreign Minister Arzu Rana Deuba, using her influence in the previous government, created 117 new positions (one secretary, 11 joint secretaries, 33 undersecretaries, 62 officers, and 4 non-gazetted first-class officers). This action ran counter to the spirit of creating a lean and efficient federal government, especially as the dominant use of technology emerges to reduce human efforts. Furthermore, based on an O&M survey, the Office of the Investment Board Nepal did secure Cabinet approval for the recruitment of a separate, investment-related service cadre, similar to those in revenue and foreign affairs, though this has not been implemented to date. Normally, such positions are created based on job evaluation, which involves a thorough assessment of whether the job created or going to be created is truly worthwhile for the organisation.

“Organisation and Management (O&M) should be carried out professionally and prepared scientifically, encompassing job identification, organisational context, job context and work conditions, work activities, requirements and outputs, performance standards, the requirement of human resources, and competencies, along with proper analysis and job descriptions,” according to experts. They further state, “Normally, a job has six to eight Key Result Areas (KRAs), and within one KRA, there could be one to five duties. If there are more than six to eight KRAs, another job must be designed for effective results.”

Unless such a detailed analysis is conducted, there is an ongoing challenge of overstaffing in some organisations, while others face understaffing. Furthermore, employee performance is not aligned with KRAs, which has caused Human Resource Management (HRM) in the public sector to operate in silos. While analysing public sector HRM based on the key HR functions, it is clear that the public sector needs to streamline these functions for effective service delivery and the satisfaction of citizens.

Recruitment and selection

Recruitment and selection are a major function of Human Resource Management (HRM). There has been a massive reform in the selection process. Not only for the civil service, but also for the permanent employees of state-owned enterprises, selection is conducted through a competitive examination process administered by the Public Service Commission (PSC). This process is transparent and merit-based. The PSC, a constitutional body, has established itself as a highly credible institution by ensuring fairness in examinations, both written and interview-based, to facilitate recruitment and promotions in the concerned government agencies. However, some contract-based employees in SoEs are still appointed based on political approach, which undermines efficiency in service delivery.

Public sector recruitment is merit-based. Conversely, recruitment in the private sector is competence-based and also considers behavioural aspects. Unlike the private sector, the public sector maintains provisions for inclusion and quotas to recruit individuals from disadvantaged and marginalised communities, symbolising equitable rights as per the constitutional promise. Most importantly, there has been decentralisation in the recruitment and selection process, and it is primarily an external function as the PSC is assigned for selection, with minimal involvement from the concerned hiring agency.

In contrast, for the private sector, this is largely an internal process. With the emergence of independent HR consulting firms, the private sector, especially regulated sectors such as banks and insurance, has begun assigning these firms for initial selection. Still, the concerned agencies retain involvement in the final selection process. The private sector has introduced more engaging terms to add appeal to HR functions. For example, recruitment and selection is often simply termed ‘talent acquisition’. Alongside these terminologies, there are specific innovations in HR practices as well.

Performance management

Performance management is the most critical element within Human Resource (HR) functions. The public sector has implemented performance management in practice, however, it is not strongly aligned with Key Result Areas. Performance management is also a fundamental part of accountability. There has been a practice of performance contracts from the Section Officer to the Secretary level, but these contracts largely focus on process-based activities rather than results-based achievements. Secretaries sign performance contracts with ministers, and ministers sign them with the prime minister. Similarly, the heads of agencies under the Office of the Prime Minister sign performance contracts with the prime minister. Chandrakala Poudel, Secretary of the Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration, has noted that although different frameworks for performance contracts exist across various ministries and agencies, the same evaluation and appraisal system is applied universally.

As the delivery of public institutions ultimately depends on citizen satisfaction, performance management is considered a crucial element for holding public servants accountable. The Office of the Auditor General (OAG) has stated that unless the supreme audit institution carries out performance audits of higher-level authorities and its recommendations are enforceable in matters of transfer and promotions, the challenge in performance management will persist as a major issue in the public sector.

In contrast, performance management in the private sector is properly aligned with KRAs, and rewards and incentives are provisioned based directly on performance. There are specific Key Performance Indicators used to measure performance like time, quality, and quantity, which are considered universal indicators. Furthermore, cost-effectiveness and satisfaction serve as additional indicators. Normally, KPIs are customised based on the specific needs of companies and organisations.

Performance evaluation should be a combination of both objective and subjective measures. Objective measures are based on quantifiable, fact-based data, such as sales numbers or deadlines met. In contrast, subjective measures capture qualitative aspects, such as teamwork, communication, and creativity, which necessarily require human judgement. A balanced approach that effectively leverages objective data while incorporating subjective evaluation ultimately provides the most complete and accurate assessment.

Training and Development

Training and development are practiced in the public sector in a more effective manner compared to performance management. Section officers are provided intensive entry-level training from the Nepal Administrative Staff College (NASC).

Ram Sharan Pudasaini, Executive Director of NASC, explains, “Entry-level training programmes last up to six months. During their service, officers are normally offered six-week training courses that support smooth transitions in government jobs. Training for undersecretary and joint secretary levels is provided for two weeks immediately after their promotions.”

The government has established training institutes based on the specialisation of services. These include the Public Finance Management Training Centre for revenue and accounting, the Co-operative Training and Research Centre for cooperatives, and the Land Management Training Centre for survey-related training. There are separate training centres for specific services such as the Agriculture Information and Training Centre, National Health Training Centre, and the Institute of Foreign Affairs (IFA), among others. These institutions provide on-the-job training. Furthermore, security agencies maintain their own training institutes, which are more decentralised.

The government also offers scholarships for the higher study of government employees, a process that is gradually becoming fairer and more transparent, according to Krishna Hari Baskota, Former Finance Secretary.

In the private sector, skill gaps are identified during both the recruitment and selection process and also throughout the job tenure. Upskilling and reskilling are mandatory during the phase of transition to another level. Moreover, the training and development efforts are also aligned with results. In recent years, training and development have been given high priority by the organised and regulated private sector, which has responded by establishing its own training institutes.

Rewards and compensation

In the public sector, there is an equal pay for equal level of job policy. Conversely, the private sector utilises performance-based pay, meaning compensation can vary significantly for the same level of job based on individual performance. However, the public sector has recently introduced incentive-based practices, such as the target-based incentives implemented in revenue administration. Incentives are primarily given in the public sector for the purpose of motivation.

In terms of rewards and compensation, the public sector offers benefits linked to the Employees Provident Fund, retirement schemes such as pensions, and paid leave for higher studies, alongside other benefits prescribed by Labour Law. The private sector, apart from performance-based pay, offers a social security scheme, bonus, and other benefits as stipulated in the country’s Labour Law.

In this regard, American psychologist Frederick Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory highlights achievement, interest, responsibility, and advancement (career growth) as the primary motivating factors in a job. He distinguishes salary, supervision, and relationship with colleagues as hygiene factors for the job. He explains that these hygiene factors are not motivating factors for performance, although they can lead to either satisfaction or dissatisfaction.

In terms of punishment, the private sector employs ‘hire and fire’ policies, which differ from the public sector, though the latter does have provisions for disciplinary action. According to Finance Secretary Ghanshyam Upadhyay, “There is a provision to take action if an employee is proven guilty. This is handled by the Division/Department head up to the officer level, by the secretary above that, and the Cabinet can take action against the secretary. However, this system is less effective.” As a result, there is no significant practice of punishment within the government, necessitating the formation of vigilance bodies for investigation and prosecution.

There is a fundamental distinction between the public and private sectors. Public institutions are primarily evaluated by citizen satisfaction, whereas the single bottom line for employees in the private sector is to support growth maximisation. In this regard, private sector HR practices might not perfectly suit the public sector. Nevertheless, the fundamental requirement remains that employee performance must be aligned with Key Result Areas. Furthermore, the private sector is dynamic and flexible in adopting new practices and altering methods for optimal efficiency, which is difficult in the public sector as it requires high-level decisions and must strictly abide by set processes and laws.

Employee relations

Employee relations are given high priority in the private sector, a practice which is currently lacking in the public sector in Nepal. Employee relations encompass several functions like executing employee retention strategies, effectively dealing with grievances, ensuring an appropriate working environment, and discreetly gathering information on key employees in vulnerable positions, as their sudden resignation could significantly impact the company. Employee relations also work to build team spirit within the organisation, identify sources of employee dissatisfaction, and address them, among other duties.

The field has evolved, particularly as more Generation Z (Gen Z) employees enter companies and organisations. Their preferences are quite distinct. They dislike ‘boss-like’ attitudes and expect their line managers or CEOs to listen to them. If this does not happen, they are prone to quitting their jobs. According to HR practitioners, “For Gen Zs, the job is less important if they are not properly treated. They could even revolt in the organisation. The job is less important for them. What is important is that they should be valued.”

“There is currently a gap in aligning jobs with Key Result Areas to some extent, but this will be fixed”

“There is currently a gap in aligning jobs with Key Result Areas to some extent, but this will be fixed”

Chandrakala Paudel, Secretary, Ministry of Federal Affairs and General Administration

There have been grievances from the public regarding service delivery, and employee performance is key to enhancing this delivery to satisfy people and citizens. Although the framework for performance contracts may vary among different government agencies, the appraisal system is similar. We must transition performance contracts to a results-based approach. In addition, the Organisation and Management (O&M) survey is need-based and requires Cabinet approval. It must be developed professionally based on identified gaps. The O&M document serves as the fundamental basis for an organisation’s job analysis, job description, and job specification. There is currently a gap in aligning jobs with Key Result Areas to some extent, but this will be fixed, and the enforcement of performance contracts will be prioritised. We believe that these steps will effectively streamline results.

“NASC conducts intensive training, particularly on administration-related affairs, and provides intensive training for the entry level”

“NASC conducts intensive training, particularly on administration-related affairs, and provides intensive training for the entry level”

Ram Sharan Pudasaini, Executive Director, Nepal Administrative Staff College

The Nepal Administrative Staff College (NASC) conducts training for the service entry level, mainly for section officers, during the course of service, and immediately after promotion to undersecretary and joint secretary levels. Entry-level training programmes are for up to six months. During-service training courses are typically offered for six weeks and support career progression, while training programmes for the undersecretary and joint secretary levels last for two weeks.

The government has established training institutes based on the specialisation of services. These include the Public Finance Management Training Centre for revenue and accounting, the Co-operative Training and Research Centre for cooperatives, and the Land Management Training Centre for survey-related training. There are also separate centres for specific services, such as the Agriculture Information and Training Centre, National Health Training Centre, and the Institute of Foreign Affairs (IFA), among others. However, these institutions primarily offer short and refresher courses. Furthermore, security agencies maintain their own training institutes, which are more decentralised.

Training and development are crucial as they necessitate upskilling and reskilling during job transitions. The NASC conducts intensive training, particularly on administration-related affairs, and provides intensive training for the entry level. The NASC typically issues a call for participation in its training programmes. Participants normally express interest based on the recommendation of their concerned ministries. As a general practice, ministries and recommending government agencies tend to prioritise senior-level employees for participation.

“Public sector is in the very early stage of introducing HR practices, and this will be strengthened in the days to come.”

“Public sector is in the very early stage of introducing HR practices, and this will be strengthened in the days to come.”

Ghanshyam Upadhyaya, Secretary, Ministry of Finance

At the strategic level of Human Resource Management, the main practice is workforce planning. Ministries and government agencies conduct an Organisation and Management (O&M) survey, which requires approval from the Cabinet. The O&M process is led by the concerned agency with involvement from the Ministry of Federal Affairs. Job analysis, scoping, and job descriptions are prepared during this O&M process. Recruitment and selection are subsequently carried out by the Public Service Commission based on the O&M survey findings. Apart from workforce planning, there is no formal HR strategy in the public sector, such as succession planning or other strategic initiatives. However, regarding HR functions, some have been successfully integrated into the public sector, including training and development and performance appraisal, in addition to recruitment and selection.

Training and development are provided based on capacity needs assessments throughout an employee’s career, following the mandatory intensive entry-level training from the Nepal Administrative Staff College. Practices such as reward and punishment and robust employee relations are utilised in other countries, but these are sorely lacking in our context. The public sector has introduced certain HR functions primarily to align employee performance with the government’s objectives and the targets set by annual and long-term plans. Performance appraisal is still isolated and needs to be linked with the performance contract. Performance is key in the public sector, and it must be aligned with fair appraisal and effective reward and punishment mechanisms. Both of these parameters are currently weak in the public sector.

If a strong reward and punishment mechanism were established within the government, the vigilance bodies might be able to shift their focus to bigger and policy-level corruption issues. Although there is a provision to take action, up to the officer level by the Division/Department head, and by the Secretary above that, with the Cabinet taking action against the Secretary, it is currently less effective. In terms of incentives and rewards, these have been implemented in certain services, such as in revenue under our ministry (Ministry of Finance), where they are provided based on the achievement of a given target. I believe the public sector is in the very early stage of introducing HR practices, and this will be strengthened in the days to come.